This article originally appeared as a chapter in “Russia Strategic Intentions White Paper,”Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) publication series, NSI, May 2019.

Presidents Faustin Archange Touadera of the Central African Republic and Vladimir Putin of Russia. (Photo: kremlin.ru)

Abstract

Russia has significantly expanded its engagements in Africa in recent years in response to perceived opportunities to access natural resources, expand weapons sales, and elevate its geopolitical posture in a region with rapidly developing emerging markets and considerable promise for growth and trade. These engagements often take the form of propping up embattled and isolated autocratic leaders of countries that are rich in natural resources. This provides Moscow considerable leverage with these leaders and the ability to undermine previously negotiated political settlements, access natural resources under opaque agreements, and weaken democratic governance standards. The United States can draw a distinction with Russia’s destabilizing role by pursuing a positive engagement strategy in Africa. This should be coupled with an assertive policy of sanctioning individuals and entities that are facilitating illicit resource diversions, deploying mercenaries, and undermining democratic processes, while calling out the lack of legitimacy and conflicts of interest facing leaders that Moscow has compromised. The United States must avoid the Cold War trap of competing with Russia for the affections of corrupt, autocratic leaders in Africa, however, as such a policy would be disastrous for Africa while not advancing US interests.

Countering the Destabilizing Fall-Out of Russia’s Pivot to Africa

Russia’s “Pivot to Africa” (Foy, Astrasheuskaya, & Pilling, 2019) has begun to take shape. In 2018, Moscow swooped into Bangui, Central African Republic (CAR) with arms and mercenaries in order to prop up the weak government of President Faustin-Archange Touadera in exchange for mineral rights. A former Russian intelligence officer is now national security advisor and Moscow is considering opening up a military base in the CAR. In the process, Russia undermined the fragile diplomatic efforts of the United Nations and France that had brought the competing factions in Bangui back from years of instability toward a path to peace. Opportunistically, Russia has simultaneously negotiated for access to mineral rights with three rebel groups contesting Touadera’s government (Plichta, 2018). Meanwhile, three Russian journalists who were investigating the role of Russian mercenaries were murdered in a targeted killing while driving in rural CAR in July 2018.

In Sudan, Russia provided diplomatic, financial, and arms support to the beleaguered government of Omar al-Bashir who, overseeing economic mismanagement and rapidly rising inflation, was ousted in a military coup in April 2019 following widespread protests to his 30 years in power. Tellingly, it was the Bashir government that hosted the alternate diplomatic process promoted by Moscow in the CAR. Khartoum hosted a similarly incongruous revised peace agreement among the main rival actors in the conflict of South Sudan, which given its oil wealth is of interest to both Sudan and Russia.

These episodes reveal a pattern of Russian support for embattled African leaders of natural resource rich countries (Burger, 2018). Subsequent natural resource access agreements are highly opaque. A combination of arms, diplomatic cover, and help in orchestrating electoral outcomes while touting a disdain for human rights and transparency standards have endeared Moscow to leaders in a host of countries including Zimbabwe, Egypt, Libya, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

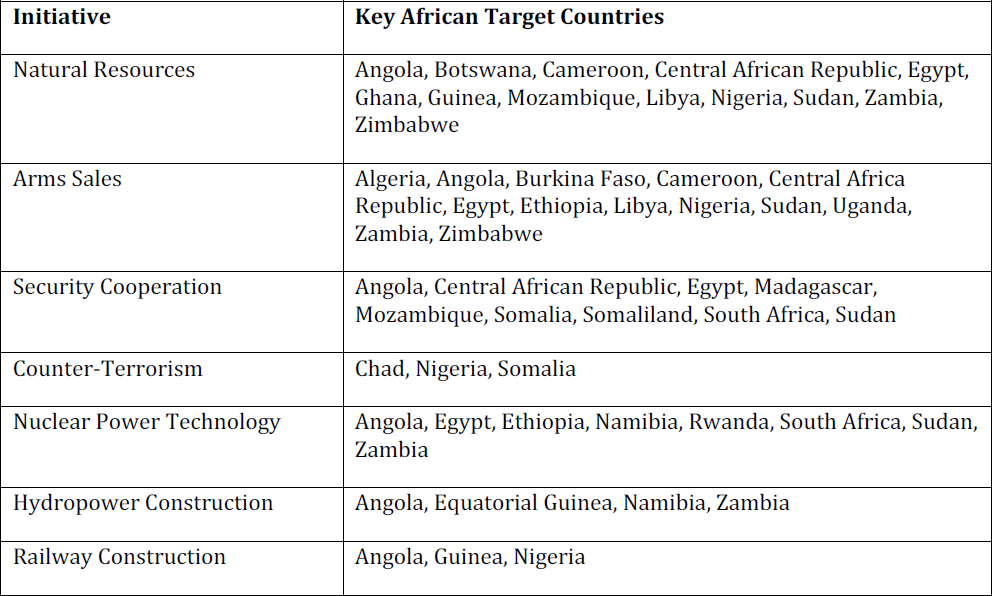

Russia’s outreach to Africa is more than short-term opportunism, however (Giles, 2013). Moscow has also strategically pursued mineral access, weapon sales, negotiated security cooperation agreements, nuclear power development, and trade relationships in selected countries in Africa. This has resulted in a steady growth of Russia’s trade with Africa over the past decade, amounting to just under $20 billion. Targeted countries include old Cold War partnerships, mineral-rich Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries, and countries with large populations and growing markets (see table).

Targeted Russian Initiatives in Africa

In short, Russia’s intentions in Africa are multifaceted. In certain circumstances it is pursuing viable trade and investment opportunities in Africa (such as for engineering and power generation projects) as do other external interlocutors. In this way, Russia presents itself as a reliable partner and supplier of needed technical expertise. Russia is hosting an Africa leaders’ summit in Sochi in October 2019 and is going all out to ensure maximum participation. Yet, in other contexts, Russia resembles a rogue actor, embracing pariah leaders, deploying mercenaries, bypassing arms embargos, and actively undermining existing internationally-brokered peace agreements so as to advance Moscow’s leverage (Luhn & Nicholls, 2019). In some cases, Libya and CAR for example, Russia appears to be applying some of the lessons from its experience in Syria where support to an isolated leader establishes a dependency relationship that gives Russia enormous regional influence that could prove highly lucrative.

Respond to Russia’s Disruptive Engagements by Reinforcing the Rule of Law

Russia’s varied engagements in Africa call for a multi-tiered policy response. To be clear, it is the destabilizing elements of Russia’s actions that are most concerning, especially those that are undermining established norms of accountable governance and the upholding of the rule of law. Importantly, then, the response from the United States should not be reflexively anti-Russian. Russia and African governments may reasonably wish to pursue cooperative partnerships. Rather, any focus on curbing Russian actions in Africa should be aimed at the destabilizing activities that Russia pursues in Africa’s weak states often with illegitimate leaders.

To underscore this distinction, the United States should make respect for the rule of law a prominent theme of its policy guidance in Africa. This theme should be a recurring message in public statements and should steer US priorities in Africa, recognizing that this principle has not always been consistently applied. Governments that are legitimately elected, respect term limits, and uphold the rule of law should gain greater diplomatic, development, and security cooperation support from the United States. Doing so establishes a clear and positive framework to guide US engagements in Africa. It also reinforces the message that the United States pursues partnerships on the continent for their mutually beneficial merit.

Such a policy framework also builds on a legacy of positive American initiatives that have enhanced stability and improved the quality of life on the continent, including such popular programs as the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), Power Africa, and the Millennium Challenge Corporation. In addition, the United States has been the world leader for years in commitments of development assistance, support for peacekeeping, foreign direct investment, and expanding access to information and communications technology in Africa.

A policy framework upholding the rule of law is not only consistent with US values, it also has contributed to better governance and thus greater stability and well-being on the continent. Notably, since the end of the Cold War, Africa’s democracies have consistently realized economic growth that is a third faster than the norm on the continent, been part of just a fraction of conflicts, and are targets of higher levels of foreign direct investment as investors seek emerging markets that are stable and respect the rule of law.

In short, legitimacy matters. By making this an operating principle of US engagements in Africa, the United States would be aligning itself with the hopeful, stable, and rules-based future to which the vast majority of Africans aspire. Doing so can also more clearly juxtapose the extralegal and destabilizing actions taken by Russia.

Raise the Costs to Russia for its Destabilizing Actions

It is the destabilizing elements of Russia’s engagements in Africa that warrant most attention. Russia is a consistent supporter of autocratic governments, opaque natural resource contracts, and arms shipments to already unstable regions in Africa. This has perpetuated the rule of repressive leaders, who have fostered institutional corruption, societal disparities, long-running conflict, and record levels of refugees and population displacement on the continent.

Russia has persisted and expanded its destabilizing activities in Africa because Moscow bears few, if any, costs for doing so. It is a high benefit-low risk calculation. Curbing Moscow’s behavior, therefore, is predicated on changing this calculus by increasing the costs Moscow faces for its destabilizing actions in Africa. These costs can take multiple forms.

The first is reputational. Russia’s propping up of unpopular regimes that are resistant to powersharing (such as in Algeria, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zimbabwe) should be publicized for both African and international audiences. These governments are using coercive means to hold on to power against the wishes of their youthful populations that are demanding more say over the national decisions affecting their lives. Russian diplomatic, financial, and military assistance enables these leaders to remain in place. Yet, the costs of these policies – heavy-handed government, stagnant living conditions, elite corruption – are being paid for by African citizens thanks, in part, to Moscow. The Russian link to instability and exclusionary regimes needs to be conveyed to African citizens – through multiple channels, including trusted media, civil society, and social media networks. This awareness-raising will create additional pressure on complicit national leaders while establishing a reputational cost for Russia. Beyond the countries in question this reputational effect will spill across borders and affect Russia’s ability to negotiate trade, investment, and security cooperation deals elsewhere on the continent.

In addition to reputational costs, changing the political calculus for Russia will entail increasing the financial costs it bears for its destabilizing actions in Africa. Those individuals or organizations involved in Russia’s opaque natural resource deals on the continent should be considered for sanctions and investigation under the Foreign Corruption Practices Act (FCPA) with the aim of denying these actors and their intermediaries’ access to the US financial system. The United States has broad jurisdiction in such cases covering any transaction that transits through, draws on a bank account in, or involves correspondence based in the United States. Implemented by the Department of Justice and the Security and Exchanges Commission, the FCPA has previously been applied to organizations operating in Russia, Nigeria, Angola, and Ghana, among others.

The United States should also consider applying provisions of the 2017 Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act for destabilizing Russian actions in Africa. The law establishes the scope for US sanctions against any country involved in transactions with Russia’s defense and intelligence sectors. This may entail Russia’s reliance on private security contractors (such as the Wagner Group in the CAR) or third-party arms dealers. Such groups provide Russia a measure of plausible deniability, however, echoing practices it has employed in the Ukraine. Consequently, an alternative approach toward these groups is to treat them as organized criminal syndicates and apply the relevant protocols (especially with regard to trafficking in firearms) under the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime as well as the legal tools embodied in the 2017 US Presidential Executive Order on Enforcing Federal Law with Respect to Transnational Criminal Organizations and Preventing International Trafficking. The United States and other rules-based international actors should also continue to support arms embargos in unstable contexts where, at times, illegitimate leaders have used violence against civilians (e.g. Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, South Sudan, and Zimbabwe). By so doing, the United States can narrow the legal space that Russia can exploit to prop up these governments (and maintain its leverage.)

The deployment of mercenaries, even if called advisers and sent with the tacit assent of an African leader, contravenes the Organization for African Unity’s 1972 Convention for the Elimination of Mercenaries in Africa. In fact, Africa was one of the earliest adopters of such a ban given the destabilizing effects that these foreign fighters have had on the continent historically. Upholding these norms should continue to be a priority.

Increasing the costs to Russian decision-makers for their initiatives that undermine such norms, and security more generally, can create incentives for Moscow to dial back its destabilizing actions in Africa.

Increase the Costs for Russia’s African Enablers

Russia gains leverage for these destabilizing actions through the complicity of often unelected and isolated African interlocutors who, lacking legitimacy, turn to Moscow for financial support or military assets. In so doing, these individuals may benefit politically or financially, though to the detriment of their societies that face greater instability and compromised sovereignty. An extension of the policy increasing the costs to Russia for its exploitative actions is to sanction African individuals who facilitate Russia’s destabilizing actions. In particular, the United States should consider imposing travel bans and asset freezes on individuals identified as responsible for cooperating with Moscow on illicit transactions, actions that result in human rights violations against their citizens, or actively undermine democratic processes or institutions.

As Russia tends to leverage its influence through illegitimate African leaders, the United States and other rules-based actors in the region should also selectively consider not recognizing these leaders as the rightful head of state. This is what the United States and 50 other countries have done in Venezuela following the fraudulent elections, coercive use of state security forces against civilians, and gross misgovernance there. The threat of this action will highlight the tenuous claim of public authority these leaders wield as well as the liability their lack of legitimacy poses. While not to be taken lightly and requiring clear guidelines, once established, this determination also provides a basis from which to obviate international recognition of public contracts that these leaders have signed. In effect, such a designation would signify that these contracts are signed with individuals rather than state authorities. A further effect of this action is to raise the risk premium for external actors attempting to gain access to a state’s sovereign assets through these compromised individuals. Implicit in this approach is avoiding the impulse to compete with Moscow for the affections of these illegitimate and unaccountable leaders. Doing so provides unwarranted leverage for these leaders who can easily play Russian and American interests off one another. Such an approach would be a replay of the Cold War outcomes observed in Africa that were marked by record levels of conflict and repressive governance. In short, the only winners in such a competition are these illegitimate leaders themselves. Under such circumstances, it is not even clear that Russia, which may gain access to some resources and a sense of prestige, comes out ahead. The costs of maintaining such kleptocratic and unstable clients can easily surpass whatever gains Moscow may realize.

Sustaining Engagements with an Emerging Africa

Given its emerging markets, natural resource wealth, strategic location, and growing importance in international fora, interest in Africa is growing among multiple external actors, not just Russia. Over 350 new embassies and consulates have been established in Africa by a wide range of foreign governments since 2010. By building on its solid foundation of engagements in Africa, the United States is well-positioned to be a part of further mutually beneficial partnerships in the future. To do so, however, will require sustained engagements. Such engagements can help set a bar for good governance and the rule of law that has direct benefits for stability, development, and ongoing investment in Africa. It simultaneously provides a clear juxtaposition with destabilizing actions undertaken by Russia. This also shifts the basis of competition to the arena of good governance on which Moscow does not have an appealing model and away from the practices of opaque contracting and propping up of authoritarian governments in which Russia has the advantage.

References

- Burger, J. (2018, November). The Return of Russia to Africa. The New African, pp. 14-21.

- Foy, H., Astrasheuskaya, N., & Pilling, J. (2019, January 22). Russia: Vladmir Putin’s Pivot to Africa. The Financial Times.

- Giles, K. (2013). Russian Interests in Sub-Saharan Africa. Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute.

- Luhn, A., & Nicholls, D. (2019, March 3). Russian Mercenaries Back Libyan Rebel Leader as Moscow Seeks Influence in Africa. The Telegraph.

- Plichta, M. (2018, November 28). France and Russia Fiddle While the Central African Republic Burns. World Politics Review.